Articoli correlati a The Souls of Black Folk: With "The Talented Tenth"...

Sinossi

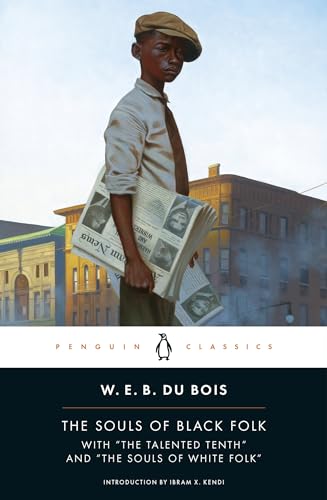

The landmark book about being black in America, now in an expanded edition commemorating the 150th anniversary of W. E. B. Du Bois’s birth and featuring a new introduction by Ibram X. Kendi, the #1 New York Times bestselling author of How to Be an Antiracist, and cover art by Kadir Nelson

“The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line.”

When The Souls of Black Folk was first published in 1903, it had a galvanizing effect on the conversation about race in America—and it remains both a touchstone in the literature of African America and a beacon in the fight for civil rights. Believing that one can know the “soul” of a race by knowing the souls of individuals, W. E. B. Du Bois combines history and stirring autobiography to reflect on the magnitude of American racism and to chart a path forward against oppression, and introduces the now-famous concepts of the color line, the veil, and double-consciousness.

This edition of Du Bois’s visionary masterpiece includes two additional essays that have become essential reading: “The Souls of White Folk,” from his 1920 book Darkwater, and “The Talented Tenth.”

For more than seventy years, Penguin has been the leading publisher of classic literature in the English-speaking world. With more than 1,800 titles, Penguin Classics represents a global bookshelf of the best works throughout history and across genres and disciplines. Readers trust the series to provide authoritative texts enhanced by introductions and notes by distinguished scholars and contemporary authors, as well as up-to-date translations by award-winning translators.

Le informazioni nella sezione "Riassunto" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

Informazioni sull?autore

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (1868–1963) was born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. He attended public schools there prior to attending Fisk University, where he received his BA degree in 1888. Thereafter he received a second BA degree, and an MA and PhD from Harvard. He studied at the University of Berlin as well. He taught at Wilberforce University and the University of Pennsylvania before going to Atlanta University in 1897, where he taught for many years. A sociologist, historian, poet, and writer of several novels, Du Bois was one of the main founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. He was a lifelong critic of American society and an advocate of black people against racial injustice. He spent his last years in Ghana, where he died in exile at the age of ninety-five.

Ibram X. Kendi (introduction) is the Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities at Boston University and the founding director of the BU Center for Antiracist Research. A contributing writer at The Atlantic and a CBS News correspondent, he is a coeditor, with Keisha N. Blain, of the #1 New York Times bestseller Four Hundred Souls and the author of many other books, including The Black Campus Movement, which won the W. E. B. Du Bois Book Prize; Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America, which won the National Book Award for Nonfiction; and three #1 New York Times bestsellers: How to Be an Antiracist; Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You, co-authored with Jason Reynolds; and Antiracist Baby, illustrated by Ashley Lukashevsky. A MacArthur Fellow and one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people in the world, Kendi lives in Boston, Massachusetts.

Estratto. © Ristampato con autorizzazione. Tutti i diritti riservati.

The Souls of Black Folk

By W. E. B. Du BoisPenguin Books

Copyright © 1996 W. E. B. Du BoisAll right reserved.

ISBN: 014018998X

Chapter One

Of Our Spiritual Strivings

O water, voice of my heart, crying in the sand,

All night long crying with a mournful cry,

As I lie and listen, and cannot understand

The voice of my heart in my side or the voice of the sea,

O water, crying for rest, is it I, is it I?

All night long the water is crying to me.

Unresting water, there shall never be rest

Till the last moon droop and the last tide fail,

And the fire of the end begin to burn in the west;

And the heart shall be weary and wonder and cry like the sea,

All life long crying without avail,

As the water all night long is crying to me.

? Arthur Symons

Between me and the other world there is ever an unasked question: unasked bysome through feelings of delicacy; by others through the difficulty of rightlyframing it. All, nevertheless, flutter round it. They approach me in a half-hesitant sort of way, eye me curiously or compassionately, and then, instead ofsaying directly, How does it feel to be a problem? they say, I know an excellentcolored man in my town; or, I fought at Mechanicsville; or, Do not theseSouthern outrages make your blood boil? At these I smile, or am interested, orreduce the boiling to a simmer, as the occasion may require. To the realquestion, How does it feel to be a problem? I answer seldom a word.

And yet, being a problem is a strange experience ? peculiar even for one whohas never been anything else, save perhaps in babyhood and in Europe. It is inthe early days of rollicking boyhood that the revelation first bursts upon one,all in a day, as it were. I remember well when the shadow swept across me. I wasa little thing, away up in the hills of New England, where the dark Housatonicwinds between Hoosac and Taghkanic to the sea. In a wee wooden schoolhouse,something put it into the boys' and girls' heads to buy gorgeous visiting-cards? ten cents a package ? and exchange. The exchange was merry, till one girl, atall newcomer, refused my card, ? refused it peremptorily, with a glance. Thenit dawned upon me with a certain suddenness that I was different from theothers; or like, mayhap, in heart and life and longing, but shut out from theirworld by a vast veil. I had thereafter no desire to tear down that veil, tocreep through; I held all beyond it in common contempt, and lived above it in aregion of blue sky and great wandering shadows. That sky was bluest when I couldbeat my mates at examination time, or beat them at a foot-race, or even beattheir stringy heads. Alas, with the years all this fine contempt began to fade;for the worlds I longed for, and all their dazzling opportunities, were theirs,not mine. But they should not keep these prizes, I said; some, all, I wouldwrest from them. Just how I would do it I could never decide: by reading law, byhealing the sick, by telling the wonderful tales that swam in my head, ? someway. With other black boys the strife was not so fiercely sunny: their youthshrunk into tasteless sycophancy, or into silent hatred of the pale world aboutthem and mocking distrust of everything white; or wasted itself in a bitter cry,Why did God make me an outcast and a stranger in mine own house? The shades ofthe prison-house closed round about us all: walls strait and stubborn to thewhitest, but relentlessly narrow, tall, and unscalable to sons of night who mustplod darkly on in resignation, or beat unavailing palms against the stone, orsteadily, half hopelessly, watch the streak of blue above.

After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian,the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with secondsight in this American world ? a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the otherworld. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense ofalways looking at one's self through the eyes of others, of measuring one's soulby the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feelshis twoness, ? an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciledstrivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alonekeeps it from being torn asunder.

The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife, ? this longingto attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better andtruer self. In this merging he wishes neither of the older selves to be lost. Hewould not Africanize America, for America has too much to teach the world andAfrica. He would not bleach his Negro soul in a flood of white Americanism, forhe knows that Negro blood has a message for the world. He simply wishes to makeit possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American, without being cursedand spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of Opportunity closedroughly in his face.

This, then, is the end of his striving: to be a co-worker in the kingdom ofculture, to escape both death and isolation, to husband and use his best powersand his latent genius. These powers of body and mind have in the past beenstrangely wasted, dispersed, or forgotten. The shadow of a mighty Negro pastflits through the tale of Ethiopia the Shadowy and of Egypt the Sphinx.Throughout history, the powers of single black men flash here and there likefalling stars, and die sometimes before the world has rightly gauged theirbrightness. Here in America, in the few days since Emancipation, the black man'sturning hither and thither in hesitant and doubtful striving has often made hisvery strength to lose effectiveness, to seem like absence of power, likeweakness. And yet it is not weakness, ? it is the contradiction of double aims.The double-aimed struggle of the black artisan ? on the one hand to escapewhite contempt for a nation of mere hewers of wood and drawers of water, and onthe other hand to plough and nail and dig for a poverty-stricken horde ? couldonly result in making him a poor craftsman, for he had but half a heart ineither cause. By the poverty and ignorance of his people, the Negro minister ordoctor was tempted toward quackery and demagogy; and by the criticism of theother world, toward ideals that made him ashamed of his lowly tasks. The would-be black savant was confronted by the paradox that the knowledge hispeople needed was a twice-told tale to his white neighbors, while the knowledgewhich would teach the white world was Greek to his own flesh and blood. Theinnate love of harmony and beauty that set the ruder souls of his people a-dancing and a-singing raised but confusion and doubt in the soul of the blackartist; for the beauty revealed to him was the soul-beauty of a race which hislarger audience despised, and he could not articulate the message of anotherpeople. This waste of double aims, this seeking to satisfy two unreconciledideals, has wrought sad havoc with the courage and faith and deeds of tenthousand thousand people, ? has sent them often wooing false gods and invokingfalse means of salvation, and at times has even seemed about to make themashamed of themselves.

Away back in the days of bondage they thought to see in one divine event the endof all doubt and disappointment; few men ever worshipped Freedom with half suchunquestioning faith as did the American Negro for two centuries. To him, so faras he thought and dreamed, slavery was indeed the sum of all villainies, thecause of all sorrow, the root of all prejudice; Emancipation was the key to apromised land of sweeter beauty than ever stretched before the eyes of weariedIsraelites. In song and exhortation swelled one refrain ? Liberty; in his tearsand curses, the God he implored had Freedom in his right hand. At last it came,? suddenly, fearfully, like a dream. With one wild carnival of blood andpassion came the message in his own plaintive cadences: ?

"Shout, O children!

Shout, you're free!

For God has bought your liberty!"

Years have passed away since then, ? ten, twenty, forty; forty years ofnational life, forty years of renewal and development, and yet the swarthyspectre sits in its accustomed seat at the Nation's feast. In vain do we cry tothis our vastest social problem: ?

"Take any shape but that, and my firm nerves

Shall never tremble!"

The Nation has not yet found peace from its sins; the freedman has not yet foundin freedom his promised land. Whatever of good may have come in these years ofchange, the shadow of a deep disappointment rests upon the Negro people, ? adisappointment all the more bitter because the unattained ideal was unboundedsave by the simple ignorance of a lowly people.

The first decade was merely a prolongation of the vain search for freedom, theboon that seemed ever barely to elude their grasp,?like a tantalizing will-o'-the-wisp, maddening and misleading the headless host. The holocaust of war, theterrors of the Ku-Klux Klan, the lies of carpetbaggers, the disorganization ofindustry, and the contradictory advice of friends and foes, left the bewilderedserf with no new watchword beyond the old cry for freedom. As the time flew,however, he began to grasp a new idea. The ideal of liberty demanded for itsattainment powerful means, and these the Fifteenth Amendment gave him. Theballot, which before he had looked upon as a visible sign of freedom, he nowregarded as the chief means of gaining and perfecting the liberty with which warhad partially endowed him. And why not? Had not votes made war and emancipatedmillions? Had not votes enfranchised the freedmen? Was anything impossible to apower that had done all this? A million black men started with renewed zeal tovote themselves into the kingdom. So the decade flew away, the revolution of1876 came, and left the half-free serf weary, wondering, but still inspired.Slowly but steadily, in the following years, a new vision began gradually toreplace the dream of political power, ? a powerful movement, the rise ofanother ideal to guide the unguided, another pillar of fire by night after aclouded day. It was the ideal of "book-learning"; the curiosity, born ofcompulsory ignorance, to know and test the power of the cabalistic letters ofthe white man, the longing to know. Here at last seemed to have been discoveredthe mountain path to Canaan; longer than the highway of Emancipation and law,steep and rugged, but straight, leading to heights high enough to overlook life.

Up the new path the advance guard toiled, slowly, heavily, doggedly; only thosewho have watched and guided the faltering feet, the misty minds, the dullunderstandings of the dark pupils of these schools know how faithfully, howpiteously, this people strove to learn. It was weary work. The cold statisticianwrote down the inches of progress here and there, noted also where here andthere a foot had slipped or some one had fallen. To the tired climbers, thehorizon was ever dark, the mists were often cold, the Canaan was always dim andfar away. If, however, the vistas disclosed as yet no goal, no resting-place,little but flattery and criticism, the journey at least gave leisure forreflection and self-examination; it changed the child of Emancipation to theyouth with dawning self-consciousness, self-realization, self-respect. In thosesombre forests of his striving his own soul rose before him, and he saw himself,? darkly as through a veil; and yet he saw in himself some faint revelation ofhis power, of his mission. He began to have a dim feeling that, to attain hisplace in the world, he must be himself, and not another. For the first time hesought to analyze the burden he bore upon his back, that dead-weight of socialdegradation partially masked behind a half-named Negro problem. He felt hispoverty; without a cent, without a home, without land, tools, or savings, he hadentered into competition with rich, landed, skilled neighbors. To be a poor manis hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom ofhardships. He felt the weight of his ignorance, ? not simply of letters, but oflife, of business, of the humanities; the accumulated sloth and shirking andawkwardness of decades and centuries shackled his hands and feet. Nor was hisburden all poverty and ignorance. The red stain of bastardy, which two centuriesof systematic legal defilement of Negro women had stamped upon his race, meantnot only the loss of ancient African chastity, but also the hereditary weight ofa mass of corruption from white adulterers, threatening almost the obliterationof the Negro home.

Continues...

Excerpted from The Souls of Black Folkby W. E. B. Du Bois Copyright © 1996 by W. E. B. Du Bois. Excerpted by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

Le informazioni nella sezione "Su questo libro" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

EUR 10,58 per la spedizione da Regno Unito a Turchia

Destinazione, tempi e costiCompra nuovo

Visualizza questo articoloEUR 2,00 per la spedizione da Irlanda a Turchia

Destinazione, tempi e costiRisultati della ricerca per The Souls of Black Folk: With "The Talented Tenth"...

The Souls of Black Folk

Da: Kennys Bookshop and Art Galleries Ltd., Galway, GY, Irlanda

Condizione: New. 1996. Reprint. Paperback. Provides insights into life at the turn of the 20th century. Series: Penguin Modern Classics. Num Pages: 288 pages, music. BIC Classification: 1KBB; HBJK; HBTB; JFSL3. Category: (G) General (US: Trade). Dimension: 196 x 129 x 14. Weight in Grams: 200. . . . . . Codice articolo V9780140189988

Quantità: 15 disponibili

The Souls of Black Folk

Da: Kennys Bookstore, Olney, MD, U.S.A.

Condizione: New. 1996. Reprint. Paperback. Provides insights into life at the turn of the 20th century. Series: Penguin Modern Classics. Num Pages: 288 pages, music. BIC Classification: 1KBB; HBJK; HBTB; JFSL3. Category: (G) General (US: Trade). Dimension: 196 x 129 x 14. Weight in Grams: 200. . . . . . Books ship from the US and Ireland. Codice articolo V9780140189988

Quantità: 15 disponibili

The Souls of Black Folk: With "The Talented Tenth" and "The Souls of White Folk" (Penguin Classics)

Da: WorldofBooks, Goring-By-Sea, WS, Regno Unito

Paperback. Condizione: Very Good. When The Souls of Black Folk was first published in 1903, it had a galvanizing effect on the conversation about race in America - and it remains both a touchstone in the literature of African America and a beacon in the fight for civil rights. W. E. B. Du Bois combines history and stirring autobiography to reflect on the magnitude of American racism and to chart a path forward against oppression. The book has been read, but is in excellent condition. Pages are intact and not marred by notes or highlighting. The spine remains undamaged. Codice articolo GOR002999580

Quantità: 1 disponibili

The Souls of Black Folk: With "The Talented Tenth" and "The Souls of White Folk" (Penguin Classics)

Da: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, U.S.A.

Condizione: Good. Good condition. A copy that has been read but remains intact. May contain markings such as bookplates, stamps, limited notes and highlighting, or a few light stains. Codice articolo M09E-02924

Quantità: 1 disponibili

Souls of Black Folk: With the Talented Tenth and the Souls of White Folk

Da: Roundabout Books, Greenfield, MA, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condizione: Very Good. Condition Notes: Clean, unmarked copy with some edge wear. Good binding. Dust jacket included if issued with one. We ship in recyclable American-made mailers. 100% money-back guarantee on all orders. Codice articolo 1614252

Quantità: 1 disponibili

Souls of Black Folk

Da: GreatBookPrices, Columbia, MD, U.S.A.

Condizione: good. May show signs of wear, highlighting, writing, and previous use. This item may be a former library book with typical markings. No guarantee on products that contain supplements Your satisfaction is 100% guaranteed. Twenty-five year bookseller with shipments to over fifty million happy customers. Codice articolo 492993-5

Quantità: 2 disponibili

The Souls of Black Folk

Da: Biblios, Frankfurt am main, HESSE, Germania

Condizione: New. pp. 288. Codice articolo 18658714

Quantità: 3 disponibili

Souls of Black Folk

Da: GreatBookPrices, Columbia, MD, U.S.A.

Condizione: As New. Unread book in perfect condition. Codice articolo 492993

Quantità: Più di 20 disponibili

Souls of Black Folk

Da: GreatBookPrices, Columbia, MD, U.S.A.

Condizione: New. Codice articolo 492993-n

Quantità: Più di 20 disponibili

The Souls of Black Folk

Da: THE SAINT BOOKSTORE, Southport, Regno Unito

Paperback / softback. Condizione: New. This item is printed on demand. New copy - Usually dispatched within 5-9 working days 236. Codice articolo C9780140189988

Quantità: Più di 20 disponibili